By Anthony Advincula, The Reporting on Health Collaborative

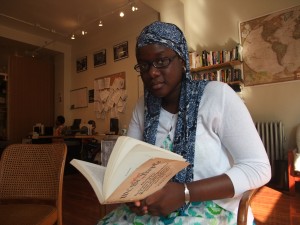

When she was 11 years old, U.S.-born Fanta Fofana witnessed immigration officers arrest her father, an immigrant from Senegal. After he was deported, Fofana, now 17, said that she often feels stressed and left out. Photo: Anthony Advincula, New America Media

NEW YORK — It takes only a few minutes for an immigration officer to arrest undocumented parents at home while their children watch. But the event can lead to a lifetime of psychological and physical consequences on children staring wide-eyed as their parents are taken away.

“It is not just a traumatic event, but it is the beginning of a series of traumatic events in the lives of these children,” said Dr. Adam Brown, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center. “That’s the bigger picture.”

Every day more than 1,000 immigrants on average are deported from the United States, and many of them are parents who were arrested and handcuffed in front of their children, before they were taken to a detention center to wait for their deportation. Over time, this means that hundreds of thousands of children are at risk of high level of trauma exposure.

While children show different responses to early trauma, depending on factors such as their age, coping mechanisms, and family support, Brown says that research shows that witnessing a parent’s arrest or deportation leads to a complex series of problems.

“These children are much more vulnerable for psychological disorders such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and depression,” he added. “Later, they are also likely to suffer from educational difficulties, have lower IQ, and end up unemployed.”

A recent report conducted by the Center for Human Rights and International Justice’s Post-deportation Human Rights Project at Boston College found that the most common effects on children who witness the forcible removal of the parent include loss of appetite, sleeping changes, crying, and feeling afraid. Although these emotional changes may lessen over time, behavioral symptoms such as withdrawal, anger and aggression persist at similar or higher levels long term.

One day that changed everything

It was a loud knock on the door.

On an early morning in 2007, immigration officers burst into an apartment in the Bronx, and Fanta Fofana was woken up by the commotion.

As her mom pleaded with the officers, Fofana recalled, they apprehended her Senegalese father, Sory. She and her five younger siblings scurried around the living room, crying.

Despite the chaos and confusion, Fofana says that the officers “didn’t show emotions” as they took Sory away.

Fofana was 11 years old and her siblings were 10, 8, 5, 4, and 2 years old. They are all U.S. citizens by birth.

Everything unfolded quickly, Fofana said. Within a few minutes, she, her siblings, and her mother were left behind without a father, which transformed their lives as a family.

“It still bothers me,” Fofana, now 17, said softly, hands clasped in her lap. Absentmindedly, she touched the edge of her blue African-print headdress that draped over her shoulders. “I am still sad.”

Despite her efforts not to dwell on her separation from her father, she admits that she feels angry and stressed. When she’s with her friends in school, she often feels as if she’s different from them.

“I feel left out,” Fofana said. “When my friends talk about their parents, I’d end up crying by myself.”

Fearing what is going to happen to her family, she says she has trouble staying focused and gets a lot of headaches.

“There’s so many things on my mind. There are times that I don’t know where to go,” she said. “My brothers, sisters and I were all born here. How could our country do this to us?”

Absence of clear policy

When immigration officers conduct a residential raid, independent public policy groups say that there is no existing protocol on how to carry out the arrest of a parent when children are around.

Raids are usually done early in the morning when family members are at home. Frequently, the officers arrest a parent without taking into consideration whether the children are witnessing the incident.

A Women’s Rights Refugee Commission report shows that this kind of operation, with no clear federal policies and procedures to handle raids and residential arrests, lead to inconsistent practices to protect the children and their psychological well-being.

The report says that, instead, decisions that can have significant impact on children’s welfare are subjectively up to the immigration officer.

In the case of Sory, Fofana found out later from her mother, Fatoumata, that when immigration officers came to their apartment, they were actually looking for a different person of African descent.

“The officers may have asked someone in the building and they pointed them to us,” Fofana said.

During residential operations, agents have a warrant that specifies the names of individuals, but that does not mean they can’t detain and ultimately deport a person not on that warrant. If they knock on a door and are allowed by an occupant to enter a home, they can question anyone present.

And, if there’s anyone deemed to have violated immigration laws in that home, they can be arrested without a warrant.

So, when Sory could not show a proof of his legal immigration status, Fofana said, the agents took him away.

Her mother, who is also undocumented, was not apprehended, allowing her to continue caring for her minor children. This decision was entirely up to the agents.

“We thought our father was coming home soon,” Fofana said.

It was more than a week later when they found out that her father was at a New Jersey detention center.

“It [arrest] happened a day after my father’s 47th birthday,” Fofana added. “That was the last time we saw him.”

Refusing to seek help

Many young people whose parents are detained or deported are unlikely to seek help at the early stage of their mental health struggles — and this can set the tone for a lifetime of chronic health challenges, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) research on adverse childhood experiences (ACE).

The CDC study on ACE says that factors that might trigger depression, anxiety, risky behaviors and physical diseases later in life have deep roots in the developmental years. In fact, CDC added, childhood adversities “are not lost but, like a child’s footprints in wet cement, are often life-long.”

With about 400,000 people being deported from the United States every year, this means that the true mental health toll on the families left behind is not being addressed.

Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, founding director of the Center for Reducing Health Disparities at the University of California-Davis, said that, for young people who have lost a parent through deportation, the sensitivity of their family condition makes them reluctant to share their experiences and express their feelings.

Many of these children have very little knowledge about mental health issues and have no support system that they can trust, he added, and so they sort out their mental health problems on their own – or ignore them in the belief that they will just go away.

“They tend to wait and wait until they could not take it any longer and they are already folding apart,” he added. “And, eventually, they have double or triple vulnerabilities, in terms of mental health impact.”

Aguila-Gaxiola is helping lead a federally funded ongoing study on the mental health effects of deportation on mixed-status children of Mexican descent, between 10 and 12 years old. He found in earlier research that those exposed to adversities, including parental deportation, at a young age are more susceptible to mental health problems.

“This kind of separation can be catastrophic for children in critical stages of their development,” he said, relating his findings to the body of research on ACE. “Childhood adversities are the strongest predictors of early onset of mental illnesses and may increase the risks of various chronic physical health conditions, such as diabetes, asthma, back pains, frequent headaches, renal problems and even cancer, in later life.”

One ACE study also showed that there is a significant relationship of childhood adversities to premature death during adulthood. People with two or three times higher exposure to childhood adversities, according to the findings, died nearly 20 years earlier on average than those without.

It’s never too late

If these children had access to proper health care, Aguilar-Gaxiola asserted, they would seek medical help. He believes that a large number of these children don’t know where to go for mental health services. And, if they are undocumented themselves, there are few options.

“It is very important to have a trusted adult who cares for them and who is committed to make them understand the importance of seeking treatment, when necessary,” he said. “Data also show that if we can do something to counter the adverse impact of these adversities, those who have been significantly traumatized could be more resilient and functional.”

For Brown, the key is to have a knowledgeable caregiver that would be able to guide for the children who face psychological and emotional struggles.

“Often, these kids are misdiagnosed because psychiatrists are very hesitant to ask trauma questions, because they are afraid to re-traumatize them,” Brown said. “But if there’s a caregiver who knows the child’s trauma history, then they’re going to have a sensitive and appropriate way to address the child’s behavior.”

In San Francisco, El Dorado Elementary School has implemented trauma-informed and restorative practices. Students who act up in school or who are found to have been exposed to violence at home, work with a therapist, along with their teachers and school administrators to provide the students a more safe and supportive learning environment.

In 2009, before the program was implemented, 674 students were sent to the principal’s office for fighting, yelling or inappropriate behavior, and 80 of them were suspended or expelled. But last year, with the help of therapists, El Dorado’s suspension rate dropped by 89 percent to just 17 students.

Aguilar-Gaxiola noted that that the optimal prevention window is between two and three years from the time that the person shows any symptoms of mental health disorder to the time that the condition begins to do long-term damage.

“If there’s an early prevention, a whole other impact can be prevented,” he said.

That impact isn’t just personal, Aguilar-Gaxiola said. It’s societal.

“If a good proportion of these children develop depression, anxiety disorder and substance abuse, there’s going to be a sizable population that will likely to suffer from marital disruptions, low-educational performances and poverty,” he said.

Keeping optimistic

Sory and Fatoumata, according to Fofana, both came from the village of Tambacounda, in Senegal. They crossed into the United States through the Canadian border.

Sory’s records showed that he violated a prior order to leave the United States in 1998, Fofana said, and so he was finally deported about four months after his arrest in 2007.

Soon after that, the trail of struggles for Fofana and her family seemed continuous.

Fatoumata suddenly had to support the entire family on one income. But she could not find a better paying job with no legal work documents.

Fofana said that they were not able to afford the rent of their Bronx apartment. They eventually were evicted and moved to a new apartment in Queens.

“It messed up my school and stuff,” Fofana added. “I have always asked my teacher for extension for my homework and school projects.”

As noted in a 2013 report by Human Impact Partners (HIP), a child’s health and educational achievement depend on the parents’ ability to provide economic stability.

“Parental detention, deportation and separation of families can put children at an educational disadvantage,” said Lili Farhang, co-author of the HIP report. “Our findings validate previous studies that these children will have fewer years of education, will face greater challenges in focusing on their schoolwork, which potentially translates into less income later as adults.”

Additionally, according to an Urban Institute study on immigration-related raids in six U.S. cities, approximately 1 in 5 children had difficulty keeping up with their grades after the raids.

The report also added that the deportation of a father leads to many deported fathers losing contact with their children.

The single mothers left behind, like Fatoumata, often have a tenuous legal status. Unlike a single breadwinner whose husband was laid off or injured, they are not eligible to receive worker’s compensation or unemployment benefits to help make ends meet.

For the remaining family members, the report added, loss of the deported person’s income can lead to housing insecurity, food insecurity — slipping from low income to poverty — and psychological distress.

For now, Fofana’s biggest concern is that her mother has been placed in removal proceedings. Through the help of an immigration advocacy group, an application to seek asylum was filed on her behalf.

Fatoumata is scheduled to see an immigration judge later this year.

“My mom tells us to be optimistic,” Fofana said. “But every day I fear that they will also take her away from us – and that will leave us with no parents.”

About Living in the Shadows: This project results from the Reporting On Health Collaborative, which involves MundoHispánico in Atlanta, New America Media in California and New York, Radio Bilingüe in Oakland, WESA Pittsburgh (an NPR affiliate), Univision Los Angeles (KMEX 34); Univision Arizona (KTVW 33), and ReportingonHealth.org. The Collaborative is an initiative of The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

About Living in the Shadows: This project results from the Reporting On Health Collaborative, which involves MundoHispánico in Atlanta, New America Media in California and New York, Radio Bilingüe in Oakland, WESA Pittsburgh (an NPR affiliate), Univision Los Angeles (KMEX 34); Univision Arizona (KTVW 33), and ReportingonHealth.org. The Collaborative is an initiative of The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

We Want to Hear from You! As the Living in the Shadows series unfolds, we welcome your ideas. You are part of the story too and we invite you to share your perspective and experiences by writing to immigranthealth@reportingonhealth.org, calling us at (213) 640-7534 or by joining the conversations on these topics on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/immigrantshealth or on Twitter at @immighealth.