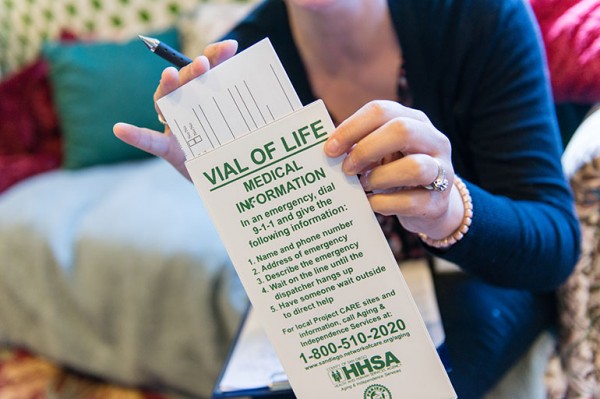

Here are four common concerns that should spark attention — only a partial list of issues that can arise. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

When Dr. Christopher Callahan examines older patients, he often hears a similar refrain.

“I’m tired, doctor. It’s hard to get up and about. I’ve been feeling kind of down, but I know I’m getting old and I just have to live with it.”

This fatalistic stance relies on widely-held but mistaken assumptions about what constitutes “normal aging.”

In fact, fatigue, weakness and depression, among several other common concerns, aren’t to-be-expected consequences of growing older, said Callahan, director of the Center for Aging Research at Indiana University’s School of Medicine.

Instead, they’re a signal that something is wrong and a medical evaluation is in order.

“People have a perception, promulgated by our culture, that aging equals decline,” said Dr. Jeanne Wei, a geriatrician who directs the Donald W. Reynolds Institute on Aging at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Judith GrahamNAVIGATING AGING

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system.

To contact Judith with a question or comment, click here.

For more KHN coverage of aging, click here.

“That’s just wrong,” Wei said. Many older adults remain in good health for a long time and “we’re lucky to live in an age when many remedies are available.”

Of course, peoples’ bodies do change as they get on in years. But this is a gradual process. If you suddenly find your thinking is cloudy and your memory unreliable, if you’re overcome by dizziness and your balance is out of whack, if you find yourself tossing and turning at night and running urgently to the bathroom, don’t chalk it up to normal aging.

Go see your physician. The earlier you identify and deal with these problems, the better. Here are four common concerns that should spark attention — only a partial list of issues that can arise:

Fatigue. You have no energy. You’re tired all the time.

Don’t underestimate the impact: Chronically weary older adults are at risk of losing their independence and becoming socially isolated.

Nearly one-third of adults age 51 and older experience fatigue, according to a 2010 study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. (Other estimates are lower.) There are plenty of potential culprits. Medications for blood pressure, sleep problems, pain and gastrointestinal reflux can induce fatigue, as can infections, conditions such as arthritis, an underactive thyroid, poor nutrition and alcohol use.

All can be addressed, doctors say. Perhaps most important is ensuring that older adults remain physically active and don’t become sedentary.

“If someone comes into my office walking at a snail’s pace and tells me ‘I’m old; I’m just slowing down,’ I’m like no, that isn’t right,” said Dr. Lee Ann Lindquist, a professor of geriatrics at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“You need to start moving around more, get physical therapy or occupational therapy and push yourself to do just a little bit more every day.”

Appetite loss. You don’t feel like eating and you’ve been losing weight.

This puts you at risk of developing nutritional deficiencies and frailty and raises the prospect of an earlier-than-expected death. Between 15 and 30 percent of older adults are believed to have what’s known as the “anorexia of aging.”

Physical changes associated with aging — notably a reduced sense of vision, taste and smell, which make food attractive — can contribute. So can other conditions: decreased saliva production (a medication-induced problem that affects about one-third of older adults); constipation (affecting up to 40 percent of seniors); depression; social isolation (people don’t like to eat alone); dental problems; illnesses and infections; and medications (which can cause nausea or reduced taste and smell).

If you had a pretty good appetite before and that changed, pay attention, said Dr. Lucy Guerra, director of general internal medicine at the University of South Florida.

Treating dental problems and other conditions, adding spices to food, adjusting medications and sharing meals with others can all make a difference.

Depression. You’re sad, apathetic and irritable for weeks or months at a time.

Depression in later life has profound consequences, compounding the effects of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, leading to disability, affecting cognition and, in extreme cases, resulting in suicide.

A half century ago, it was believed “melancholia” was common in later life and that seniors naturally withdrew from the world as they understood their days were limited, Callahan explained. Now, it’s known this isn’t so. Researchers have shown that older adults tend to be happier than other age groups: only 15 percent have major depression or minor variants.

Late-life depression is typically associated with a serious illness such as diabetes, cancer, arthritis or stroke; deteriorating hearing or vision; and life changes such as retirement or the loss of a spouse. While grief is normal, sadness that doesn’t go away and that’s accompanied by apathy, withdrawal from social activities, disturbed sleep and self-neglect is not, Callahan said.

With treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and anti-depressants, 50 to 80 percent of seniors can expect to recover.

Weakness. You can’t rise easily from a chair, screw the top off a jar, or lift a can from the pantry shelf.

You may have sarcopenia — a notable loss of muscle mass and strength that affects about 10 percent of adults over the age of 60. If untreated, sarcopenia will affect your balance, mobility and stamina and raise the risk of falling, becoming frail and losing independence.

Age-related muscle atrophy, which begins when people reach their 40s and accelerates when they’re in their 70s, is part of the problem. Muscle strength declines even more rapidly — slipping about 15 percent per decade, starting at around age 50.

The solution: exercise, including resistance and strength training exercises and good nutrition, including getting adequate amounts of protein. Other causes of weakness can include inflammation, hormonal changes, infections and problems with the nervous system.

Watch for sudden changes. “If you’re not as strong as you were yesterday, that’s not right,” Wei said. Also, watch for weakness only on one side, especially if it’s accompanied by speech or vision changes.

Taking steps to address weakness doesn’t mean you’ll have the same strength and endurance as when you were in your 20s or 30s. But it may mean doctors catch a serious or preventable problem early on and forestall further decline.

KHN’s coverage related to aging & improving care of older adults is supported by The John A. Hartford Foundation.

We’re eager to hear from readers about questions you’d like answered, problems you’ve been having with your care and advice you need in dealing with the health care system. Visit khn.org/columnists to submit your requests or tips.

When Dr. Christopher Callahan examines older patients, he often hears a similar refrain.

“I’m tired, doctor. It’s hard to get up and about. I’ve been feeling kind of down, but I know I’m getting old and I just have to live with it.”

This fatalistic stance relies on widely-held but mistaken assumptions about what constitutes “normal aging.”

In fact, fatigue, weakness and depression, among several other common concerns, aren’t to-be-expected consequences of growing older, said Callahan, director of the Center for Aging Research at Indiana University’s School of Medicine.

Instead, they’re a signal that something is wrong and a medical evaluation is in order.

“People have a perception, promulgated by our culture, that aging equals decline,” said Dr. Jeanne Wei, a geriatrician who directs the Donald W. Reynolds Institute on Aging at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Judith GrahamNAVIGATING AGING

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system.

To contact Judith with a question or comment, click here.

For more KHN coverage of aging, click here.

“That’s just wrong,” Wei said. Many older adults remain in good health for a long time and “we’re lucky to live in an age when many remedies are available.”

Of course, peoples’ bodies do change as they get on in years. But this is a gradual process. If you suddenly find your thinking is cloudy and your memory unreliable, if you’re overcome by dizziness and your balance is out of whack, if you find yourself tossing and turning at night and running urgently to the bathroom, don’t chalk it up to normal aging.

Go see your physician. The earlier you identify and deal with these problems, the better. Here are four common concerns that should spark attention — only a partial list of issues that can arise:

Fatigue. You have no energy. You’re tired all the time.

Don’t underestimate the impact: Chronically weary older adults are at risk of losing their independence and becoming socially isolated.

Nearly one-third of adults age 51 and older experience fatigue, according to a 2010 study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. (Other estimates are lower.) There are plenty of potential culprits. Medications for blood pressure, sleep problems, pain and gastrointestinal reflux can induce fatigue, as can infections, conditions such as arthritis, an underactive thyroid, poor nutrition and alcohol use.

All can be addressed, doctors say. Perhaps most important is ensuring that older adults remain physically active and don’t become sedentary.

“If someone comes into my office walking at a snail’s pace and tells me ‘I’m old; I’m just slowing down,’ I’m like no, that isn’t right,” said Dr. Lee Ann Lindquist, a professor of geriatrics at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“You need to start moving around more, get physical therapy or occupational therapy and push yourself to do just a little bit more every day.”

Appetite loss. You don’t feel like eating and you’ve been losing weight.

This puts you at risk of developing nutritional deficiencies and frailty and raises the prospect of an earlier-than-expected death. Between 15 and 30 percent of older adults are believed to have what’s known as the “anorexia of aging.”

Physical changes associated with aging — notably a reduced sense of vision, taste and smell, which make food attractive — can contribute. So can other conditions: decreased saliva production (a medication-induced problem that affects about one-third of older adults); constipation (affecting up to 40 percent of seniors); depression; social isolation (people don’t like to eat alone); dental problems; illnesses and infections; and medications (which can cause nausea or reduced taste and smell).

If you had a pretty good appetite before and that changed, pay attention, said Dr. Lucy Guerra, director of general internal medicine at the University of South Florida.

Treating dental problems and other conditions, adding spices to food, adjusting medications and sharing meals with others can all make a difference.

Depression. You’re sad, apathetic and irritable for weeks or months at a time.

Depression in later life has profound consequences, compounding the effects of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, leading to disability, affecting cognition and, in extreme cases, resulting in suicide.

A half century ago, it was believed “melancholia” was common in later life and that seniors naturally withdrew from the world as they understood their days were limited, Callahan explained. Now, it’s known this isn’t so. Researchers have shown that older adults tend to be happier than other age groups: only 15 percent have major depression or minor variants.

Late-life depression is typically associated with a serious illness such as diabetes, cancer, arthritis or stroke; deteriorating hearing or vision; and life changes such as retirement or the loss of a spouse. While grief is normal, sadness that doesn’t go away and that’s accompanied by apathy, withdrawal from social activities, disturbed sleep and self-neglect is not, Callahan said.

With treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and anti-depressants, 50 to 80 percent of seniors can expect to recover.

Weakness. You can’t rise easily from a chair, screw the top off a jar, or lift a can from the pantry shelf.

You may have sarcopenia — a notable loss of muscle mass and strength that affects about 10 percent of adults over the age of 60. If untreated, sarcopenia will affect your balance, mobility and stamina and raise the risk of falling, becoming frail and losing independence.

Age-related muscle atrophy, which begins when people reach their 40s and accelerates when they’re in their 70s, is part of the problem. Muscle strength declines even more rapidly — slipping about 15 percent per decade, starting at around age 50.

The solution: exercise, including resistance and strength training exercises and good nutrition, including getting adequate amounts of protein. Other causes of weakness can include inflammation, hormonal changes, infections and problems with the nervous system.

Watch for sudden changes. “If you’re not as strong as you were yesterday, that’s not right,” Wei said. Also, watch for weakness only on one side, especially if it’s accompanied by speech or vision changes.

Taking steps to address weakness doesn’t mean you’ll have the same strength and endurance as when you were in your 20s or 30s. But it may mean doctors catch a serious or preventable problem early on and forestall further decline.

KHN’s coverage related to aging & improving care of older adults is supported by The John A. Hartford Foundation.

We’re eager to hear from readers about questions you’d like answered, problems you’ve been having with your care and advice you need in dealing with the health care system. Visit khn.org/columnists to submit your requests or tips.