Advocates are pushing to abolish the office in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

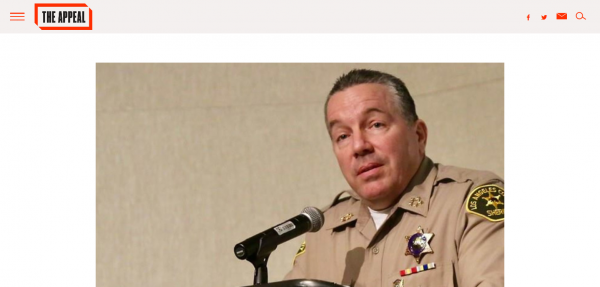

When Alex Villanueva was sworn in as sheriff of Los Angeles County in December 2018, people hoped he would get tough on the department, which had developed a reputation for brutality and corruption.

Los Angeles sheriff’s deputies had organized themselves into secret societies— with matching tattoos and names like “Jump Out Boys” and “Grim Reapers”—whose sole purpose was to perpetuate violence, mostly on prisoners and sometimes on each other. A prior sheriff, Lee Baca, was convicted in 2017 for assisting in a plan to interfere with an FBI investigation into Los Angeles jail conditions (which included allegations of routine abuse by deputies) and of lying to prosecutors.

But advocates say it’s becoming clear to the community that Villanueva is not the force of change he claimed to be. Rather than cleaning house, he created a “truth and reconciliation” committee to re-evaluate the firing of deputies by his immediate predecessor, Jim McDonnell. He ultimately rehired or ended the internal investigations of 45 employees, some of whom were accused of criminal conduct like child abuse, domestic violence, or having sex with prisoners. The county’s inspector general recently found that 31 out of those 45 were closed without explanation.

In response, some reformers in Los Angeles are putting forth a new solution: abolish the office altogether.

Inside the LA Sheriff’s Department

The Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department is the largest in the country, with over 9,000 deputies and another 9,000 staff members. Its jurisdiction covers the nation’s largest jail (with an average of 22,000 detainees on any given day), 42 cities, and terrain as diverse as deserts, mountains, and oceans. It also has a $3 billion budget.

But its size has allowed the sheriff and his deputies to amass power and often go unchecked, as shown by the recent allegations of violence.

Under California law, elected sheriffs are permitted to run the department as they wish. Although Los Angeles County’s Board of Supervisors has expressed its disapproval of Villanueva, there is little the board can do. Though California law theoretically allows the state attorney general, Xavier Becerra, to oversee, and possibly remove, a county sheriff, California AGs rarely get involved in local scandals. (When she was AG, Kamala Harris didn’t step in during the Orange County scandal over jailhouse informants, for instance.) Becerra’s office has in fact been partnering with the sheriff’s department.

“No office is less accountable or more reliable in producing scandal.

Joe Mathews / San Francisco Chronicle

That’s one reason some advocates think a radical change is needed. In January, an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle argued that the sheriff’s office should be eliminated throughout California. “No office is less accountable or more reliable in producing scandal,” wrote the author, Joe Mathews. Although police chiefs can be fired by mayors or city councils, sheriffs cannot. Sheriffs face elections every four years and are thus accountable to voters, but the incumbent usually has an advantage in elections, regardless of his performance. (Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, for instance, was elected six times.)

Though Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department has had more turnover of late, the entrenched politics of the office have been hard to shake. Many of the people rehired by Villaneuva had faced serious misconduct claims. For example, Deputy Caren Mandoyan, who was recently rehired, was fired in 2016 by McDonnell because an ex-girlfriend accused him of domestic violence and stalking, which Mandoyan allegedly lied about when asked in a hearing. (He was not criminally convicted.) Sheriff Villanueva said that “exculpatory information” had been excluded from hearings regarding the case and Mandoyan’s rehiring was recommended by the truth and reconciliation panel. (The panel, according to the Los Angeles Times, consists of three members of Villaneuva’s command staff. The Board of Supervisors is questioning the legality of the panel.)

Outside the truth and reconciliation process, Villaneuva also recently reinstated another deputy, Michael Courtial, who was fired for pulling a man out of his truck and punching him repeatedly, as well as four more deputies.

When it came to the department’s internal investigation into sheriff’s deputy gangs, Villanueva seemed to back off on pursuing any investigation and minimized the accusations. He publicly called the violent incidents “hazing run amok,” by way of dismissal. He has also made critical remarks about new sheriff’s department guidelines intended to reduce the use of force in the Los Angeles County Jail, calling them a “social experiment” that backfired and put lives at risk.”

Villanueva’s office did not respond to requests for comment or reply to questions that were emailed to his office.

Villanueva has clashed repeatedly with the Board of Supervisors, which doesn’t have the authority to set sheriff’s department policy, but does set the sheriff’s annual budget and the budgets of other county departments. In March, the board condemned Villaneuva for rehiring previously fired deputies, arguing that these actions were reversing previous attempts to root out misconduct.

Sheila Kuehl, a member of the board who has been particularly outspoken about the rehiring of Mandoyan, said, “The new sheriff did not have the authority simply to reinstate a person who had been terminated.” The board filed a lawsuit in March over the rehiring of Mandoyan that is now pending. (Mandoyan has also filed a countersuit against the board.) The lawsuit is scheduled for a hearing in June, right before the budget is finalized.

Villaneuva has told reporters that the decision to reinstate Mandoyan was his call—and it was. “I am actually assuming the proper role of the sheriff, which is to run the Sheriff’s Department,” he recently told the Los Angeles Times. “I don’t tell the board how to do their jobs, and I don’t think they have either the legal authority or right to dictate how I, as an elected official and the sheriff, run the Sheriff’s Department. That’s why the voters elected me.”

The drive to eliminate the office

Though sheriffs have arguably become less important with the rise of city police departments, many of their offices have still grown larger, hiring more people every year.

As in Los Angeles, it’s not always clear who can prosecute or remove errant sheriffs, mostly because neither happens very often. (One exception is the removal of Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel for his alleged inaction in the Parkland, Florida, school shooting. He is appealing his removal.)

The federal government has rarely if ever stepped in to curb sheriffs, and it seems unlikely to do so now.

Even muddier is the question of whether sheriffs can be eliminated from the law enforcement ecosystem entirely. For example, in 2002, voters in Los Angeles County agreed to restrict all county term limits to three four-year terms. But Lee Baca argued that the term limit didn’t apply to his office, which was enshrined in the state Constitution. He won.

Because most sheriffs derive their authority from state constitutions, eliminating the office requires an amendment that, in most cases, must be approved by voters. But that’s not out of the question.

In Connecticut, jails and other sheriff-like duties are under state authority. In 2000, voters agreed to pass a constitutional amendment to eliminate the position of sheriff, and all deputies and most elected sheriffs transitioned to the new statewide system, becoming state marshals and keeping most of the same duties.

The campaign to get rid of sheriffs in Connecticut (which had eight elected sheriffs, one for each county, since Colonial times) was inspired by a series of corruption scandals. In 1999, Sandra Caruso, then 33, was arrested for failing to appear in court for a traffic charge. Multiple detainees raped her in the back of a prisoner transport van as sheriff’s deputies sat in the front seat while, according to Caruso, she cried and screamed for help. The incident helped push voters to action.

In Missouri, St. Louis County officials decided in 1954 to create a county police department rather than a sheriff’s office. (There is a sheriff with minor duties, who is appointed.) They were able to do so, in part, because the office of sheriff was removed from Missouri’s Constitution.

Riley County, Kansas, created a consolidated county police department in 1972 to replace the sheriff’s office, but only after the state rewrote the law to allow certain counties to decide what kind of police presence they wanted. (Rural regions and the state sheriffs’ association opposed the bill, but voters passed it anyway.)

And voters in Miami-Dade County in Florida also eliminated the position of sheriff in the 1960s, wrapping the jobs associated with sheriffs into the county police force. (The move came after various corruption scandals, including one where deputies agreed to look the other way as burglars stole from wealthy homeowners, as long as the officers got a cut of the profits.) Miami-Dade is a “home rule” county, meaning it has power under the state Constitution to determine its own governing structure. The decision didn’t stick, however. The Florida Sheriffs Association lobbied for a bill, passed in 2018, that required Miami-Dade to re-establish its sheriff’s office.

The country is in a time in which the office of sheriff seems more relevant than ever. President Trump has tied himself to the National Sheriffs’ Association and invites sheriffs to the White House for bill vetoes and ceremonies. He is also consulting with them on immigration policy. The federal government has rarely if ever stepped in to curb sheriffs, and it seems unlikely to do so now.

So California advocates are considering local challenges. Kate Chatfield, an attorney who works on criminal law and policy, believes the qualifications for sheriff should change at the very least. “Given the numbers of people in our jails and the number of people with whom deputies interact with on the streets who suffer from mental illness, addiction, and other health problems, there is every reason to believe that an elected Sheriff should be a person who has worked in public health rather than coming up through the ranks of law enforcement,” she wrote in an email.

Chatfield also suggests that counties could follow a model previously created by Santa Clara County in which the Department of Correction became a separate entity, under the control of the Board of Supervisors, rather than under the sheriff. Legislators could enact laws that would empower such independent county departments to deputize people working for these agencies.

And just this month, Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, whose home county Sacramento has also struggled with sheriff accountability, proposed Assembly Bill 1185, which would give county officials like the Board of Supervisors in Los Angeles more power to create oversight boards that can force the sheriff to be more transparent. California Supreme Court precedent says the board can investigate the sheriff’s office but cannot force the sheriff to change his policies. AB 1185 would change that. Although it’s not a big step, it’s a modest one that would make Villaneuva and others more accountable.

Still, some scholars say nothing short of eliminating the office will work. Last year, James Tomberlin, now a judicial law clerk, wrote a note for the Virginia Law Review calling for change: “The critical consensus today is that policing requires robust regulation, and it is evident in studying sheriffs that elections alone are not sufficient to regulate law enforcement. What perhaps made the sheriff attractive during westward expansion makes it obsolete at best and dangerously anachronistic at worst today by preventing local governments from acting as a meaningful check on the office’s powers and holding the sheriff accountable.” In other words, it’s not the Wild West anymore■