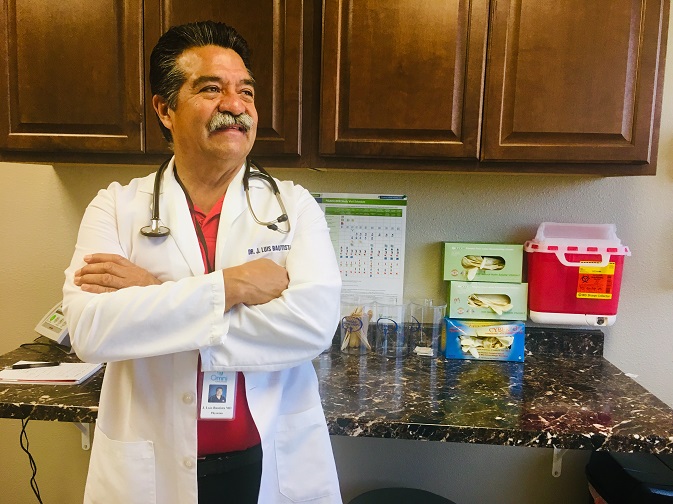

As a boy, Dr. J. Luis Bautista picked fruit alongside his parents and nine siblings in Ventura County. “I pledged in medical school to help these people in the farm fields,” he says. (John M. Glionna for Kaiser Health News)

FRESNO, Calif. — On the 15-mile drive between his two Central Valley medical clinics, Dr. J. Luis Bautista often passes armies of farmworkers stooped over in the fields, picking onions, melons and tomatoes.

Most of the 30,000 annual office visits to his small staff of doctors and nurses in downtown Fresno and the nearby rural town of Sanger are by these farmworkers. Many of them are undocumented.

The 64-year-old physician has personal insight into the struggles of these laborers: He was once one of them. As a boy, he picked fruit alongside his parents and nine siblings in Ventura County. The family made $4,000 a year back then, a little over $30,000 in today’s dollars — rarely enough to spare for doctor’s visits.

These days, Bautista sees that many farmworkers still lack the transportation, money or time off from work to treat injuries, let alone seek preventive medical care. Plus, there is the heightened fear that by seeking medical treatment they might be exposed to federal immigration authorities.

“I pledged in medical school to help these people in the farm fields,” said Bautista. “I knew how it felt not to have anything, not to have the money to go to a doctor.”

Now he treats them whether or not they have money — or legal documents. “We never say no to patients,” he said.

President Donald Trump’s campaign pledge to deport an estimated 11 million immigrants who have entered the U.S. illegally has fostered fear among farmworkers nationwide. Terrified they’ll be caught in an immigration dragnet, farm laborers across the San Joaquin Valley without U.S. citizenship or official documents avoid driving to see a doctor or visit an emergency room.

Although California law strictly limits the state’s cooperation with U.S. immigration enforcement, some jurisdictions outside the Central Valley have decided to participate in federal efforts to detain undocumented workers. Many here fear that local officials will soon join them, Bautista said.

Farmworkers also worry that personal information housed in doctors’ offices could find its way into the hands of federal authorities. And some fear that if they enroll in programs for low-income residents, they’ll later be denied permanent residence, the so-called green card, or U.S. citizenship.

The Trump administration has proposed a federal rule change that would make it harder for legal immigrants to get green cards if they have received certain public assistance benefits, including food stamps, housing subsidies and Medicaid — the government-funded health care program for people with low incomes.

“Many people don’t know what the government will do,” Bautista said. “They tell me that one reason they don’t go to the doctor is over fear they’ll be reported.”

Bautista’s two clinics provide a haven for immigrants burdened by these concerns. Patients are never asked about their immigration status, and the staffs have set up protocols in case the offices are raided by immigration authorities.

“I feel secure with him,” said Julia Rojas, a 45-year-old undocumented mother of five who has picked oranges in Fresno County for two decades. “He’s one of us.”

Bautista accepts as payment whatever his patients can offer: onions, handmade key chains, eggs, even live chickens.

Dan Baradat, a Fresno personal injury lawyer who has handled cases involving migrant workers, said Bautista’s clinics are indispensable to the Central Valley’s poorer residents. “They’re stand-up people who provide care to people who could not otherwise afford it,” he said.

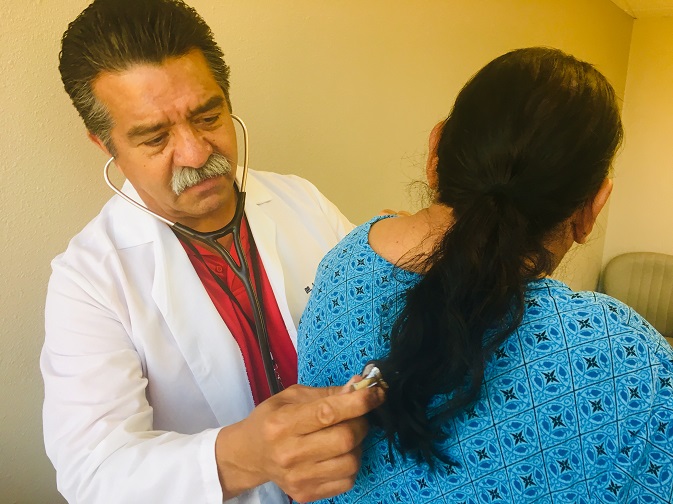

Dr. J. Luis Bautista, a former farmworker, runs two clinics in California’s Central Valley providing care — often free of charge — for migrants who don’t have money and are deeply worried about the federal government’s hard-line stance on immigration. (John M. Glionna for Kaiser Health News)

Bautista’s clinics are among a network of federally supported community clinics that provide care for nearly 1 million migratory and seasonal agricultural workers and their families around the U.S. But few providers have a better connection to the community they serve than Bautista, who in 2013 founded a nonprofit that raises money to assist low-income farm families with food and clothing, and provides scholarships to send their children to college.

Born in Fresno, Bautista was deported with his parents when he was just 3 months old. He lived in Mazatlán, Mexico, until he returned to the U.S. at age 12.

In 1979, at age 24, he was picking lemons when his mother came running out to the fields with the letter announcing he’d been admitted to medical school. She’d always been big on education for her 10 children.

Bautista attended the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and did his residency in internal medicine at the University of Nevada-Reno.

Today, two of Bautista’s four sons are also doctors. A third son, whom he adopted, is a physician assistant, as is his son-in-law, who was a farmworker before joining the clinic. His fourth son is the clinic manager. All of them know that fear of deportation is affecting farmworkers’ health.

Dr. Ed Zuroweste, founding medical director of the nationwide Migrant Clinicians Network, said a recent survey of providers within the organization underlined these fears.

“What we’re seeing on the front lines is that farmworkers and their families are not coming in for regular appointments as frequently as they had before,” he said.

Bautista said many undocumented farmworkers rely on home remedies to treat ailments such as diabetes and high blood pressure, often until it’s too late for effective medical treatment. “By the time I see many diabetic patients, their feet are already necrotic and we have to amputate,” Bautista said. “It’s terrible to see.”

Jose Jimenez, a former farmworker, said his father, who is not in this country legally, was too afraid to drive to Bautista’s office, even after developing signs of melanoma on his face. His dad’s fears were heightened last year following the death of an undocumented couple, the parents of six children, whose van overturned while they were fleeing federal immigration officers in nearby Delano.

“He was even afraid to drive to the supermarket,” said Jimenez, 30. “He knew that if he was picked up, he’d be deported. For a close-knit family like ours, that would mean losing everything.” But Jimenez finally persuaded his father to visit Bautista.

Bautista’s clinics are on guard against U.S. immigration officials, known in this community as la migra.

Law enforcement officials requesting records are asked for a warrant, and staff members are on the lookout for intruders. “By the time any ICE officers got inside the office,” Bautista said, “we’d have people hiding in the restrooms.”

Julia Rojas said her fears of deportation almost killed her. Years ago, before she began seeing Bautista, she chose to ignore the piercing pain in her lower abdomen. In the U.S. without papers and afraid to drive, she spent nearly a day drinking mint leaves in hot water — a remedy her mother used for stomach pain back in Mexico.

Unable to stand the spasms, she finally went to the nearest emergency room, where doctors removed her gall bladder. “Among undocumented workers in the fields, we have a dark little joke,” Rojas said. “You can survive out here. Just don’t get sick.”