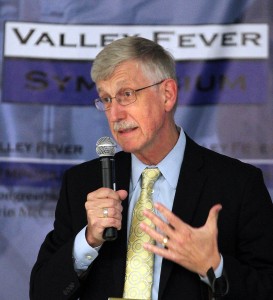

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Dr. Tom Farieden, center, director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, answers questions from valley fever patients during a community forum at the Valley Fever Symposium held in Bakersfield at the Kern County Department of Public Health Monday. At left is Dr. Royce Johnson, professor of medicine at UCLA and Kern Medical Center’s chief of infectious disease. At right is Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health.

By Tracy Wood

The Center for Health Journalism Collaborative

For seven years, Dr. George Thompson at the University of California, Davis, collected DNA samples from patients for research into valley fever.

He sought funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest funder of primary biomedical research in the U.S., but could not secure any money to pursue his inquiry: Do genes protect some people from getting sick after inhaling the fungus that causes valley fever?

But things have changed dramatically. The federal agency, which long ignored the disease that mostly affects people in Arizona and California, is now providing critical support to multiple studies that could yield new insights into valley fever. The fledgling research makes good on promises made by the NIH in the wake of an investigative year-long series on valley fever by the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative and a major symposium by the NIH and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Bakersfield that followed.

“We’re just on the cusp of doing some very exciting things,” said Dr. Steven M. Holland, director of the NIH’s Division of Intramural Research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Gene study gets started

The Coccidioides — or cocci — fungus is part of the same family as molds and mushrooms. Its spores are so tiny they can’t be seen without a microscope. The fungus lives in the soil but during dust storms, construction or other events that stir up the dust, the spores are lifted into the air and into the lungs of humans and animals. Most people develop an immunity, but for those who do not the impact can be devastating, even deadly.

Casey Christie / The Californian

Dr. Mike Lancaster, laboratory director at the Kern County Public Health Services Department, speaks on Modern Problems in Valley Fever Diagnosis to Tuesday’s crowd at Cal State Bakersfield during the final day of the Valley Fever Symposium in Bakersfield.

Why some people are more susceptible remains a mystery. That’s in part because the disease is hard to study. The same fungus that causes the disease poses a significant danger to the researchers themselves. They have to wear safety masks and use other tools to protect themselves from breathing in spores.

“This one has been a tough one,” said Dr. Dennis Dixon, chief of the NIH’s Bacteriology and Mycology Branch, “It’s hard for the patients, hard for the doctors and hard for the researchers.”

It’s also been hard to secure funding to study the disease. Thompson, an associate professor of clinical medicine at UC Davis, obtained DNA from 650 volunteer patients over seven years, without any big grants to allow him to do the necessary lab studies to make sense of the samples. All he had was the hope that he could make use of the DNA down the road.

Patients “were just so excited someone’s working on it,” Thompson said. “It’s been really a labor of love.”

For years scientists have asked why the overwhelming majority of people inhale the cocci spores and never show signs of sickness. Others, however, develop flu-like symptoms or pneumonia but recover without serious harm. And then there are the few who develop severe illnesses and even die.

Researchers believe that most people may have a genetic makeup that automatically fends off the cocci fungus. Thompson said his first attempt to secure funding from the NIH to test this theory failed, but he continued to have ongoing discussions with the agency.

In 2012, the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative, a consortium of news outlets led by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, began a year-long investigative series on valley fever.

The collaborative’s reporting – more than 50 stories – documented the need for more research, treatment, physician and consumer education and investment to lessen the disease’s devastating toll.

Casey Christie / The Californian

Many attended the second day of the Valley Fever Symposium at Cal State Bakersfield including attorney David Larwood, President of Valley Fever Solutions, third from right in the front row and California Assemblywoman Shannon Grove, R-Bakersfield, seated next to Larwood.

Following the series, U.S. Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) brought the heads of the NIH and the CDC to Bakersfield, in September 2013, for the most high profile scientific and public gathering ever focused on the disease. At the time, McCarthy was the House Republican whip, and he currently is the House Majority Leader.

“We all recognize that there’s more that needs to be done,” Dr. Francis Collins, NIH’s director, told the crowd in Bakersfield in 2013. “There’s so many unknowns.”

In 2014, the NIH agreed to add Thompson’s DNA samples to an existing genetic studies project being conducted by the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mass. Thompson hopes to see initial results from the study next year.

The Broad Institute, a joint initiative between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, has been studying genes for more than a decade, looking for ways to improve treatment of illnesses. Broad researchers will analyze 150 patients who had severe valley fever and compare their DNA to patients who were infected with the disease without serious complications. The researchers will look at the “genetic difference between those who did great and those who did not,” Thompson said.

Casey Christie / The Californian

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, talks on NIH research and valley fever during the second day of the Valley Fever Symposium at Cal State Bakersfield on Tuesday.

The NIH is also playing a key role in another study looking into genetic susceptibility, this one in conjunction with the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Tucson.

The center’s director, Dr. John Galgiani, has been researching the disease for more than three decades. In 2008, Galgiani had a teenage patient who had severe valley fever and medications weren’t working.

Galgiani sent the boy to Holland’s NIH center in Bethesda, Maryland and through testing they learned the boy had gene mutations.

“As a result of this initial breakthrough other patients were found to have mutations in other genes,” Galgiani said. “The implication was if they didn’t have the mutation,” they wouldn’t have developed valley fever.

Since then, Holland’s group has treated at least 41 severely ill valley fever patients referred by Galgiani and other doctors.

Zeroing in on genes that predispose people to severe valley fever reactions could make an important difference when it comes to prevention. Those who know they are vulnerable to infection could make sure they stay indoors during dust storms and avoid occupations like construction that stirs up the soil.

Does early treatment make a difference?

At the same symposium where NIH’s director Collins promised more of a focus on valley fever, he also announced plans for a clinical trial to find better ways to treat the disease.

“It will take some time to mount this trial, to plan it, to put it forward, but I just want to assure all of you from this part of California that we’re serious about trying to get some of those answers even in the face of difficult budget times,” Collins said.

“It will take some time to mount this trial, to plan it, to put it forward, but I just want to assure all of you from this part of California that we’re serious about trying to get some of those answers even in the face of difficult budget times,” Collins said.

Two years later, in June 2015, NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases moved the clinical trial forward by awarding $5 million to the Duke Human Vaccine Institute at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

That trial is now getting underway. More than 1,000 patients are being recruited in California and Arizona to see if early treatment with the drug fluconazole will block the cocci fungus from causing severe illness by halting the disease’s migration to bones, organs, and the brain. Currently many patients are misdiagnosed for weeks while doctors treat them for the flu or pneumonia. Once valley fever is diagnosed, fluconazole is the main drug doctors use to control the disease, but it is often prescribed too late.

Depending on their progress, the researchers could receive an additional $4 million. Duke is working with doctors at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, the University of Arizona, and Banner Health in Tucson.

Casey Christie / The Californian

Former Rep. Bill Thomas , R-Bakersfield, and Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Bakersfield, got together before Tuesday’s Valley Fever Symposium at Cal State Bakersfield.

Patients will be recruited in areas with a high concentration of valley fever cases, including Bakersfield and the Antelope Valley region of Los Angeles County in California and the Phoenix and Tucson regions of Arizona. Half of the patients will be given fluconazole and the other half will receive a placebo.

Dr. Royce Johnson, an infectious disease specialist at Kern Medical has been treating and studying valley fever cases for more than 40 years. He’s hopeful the Duke study will improve treatments and increase public and medical awareness.

“It’s been impossible to interest private industry in doing any study on cocci to speak of,” Johnson said. “The drugs that we use to treat cocci are all approved for something other than cocci, and we use them to treat cocci.”

Because, for now, that’s all we have, Johnson said.