Girl in May 1st March in Los Angeles, CA Photo by Ruben TapiaBy Zaidee Stavely

By Zaidee Stavely

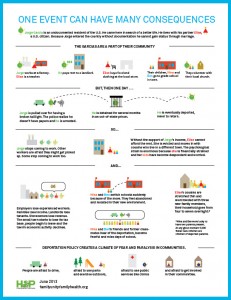

After calling police in San Francisco to report domestic violence, Sonia Cauich says she was detained without being charged for three days, in order to be handed over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Her three children, who were 11 years, 3 years, and 6 months old at the time, were left home alone.

“My son who was 11 knows how to take care of his brother and he knew how to get milk ready for the baby,” Cauich recalled, in Spanish.

Cauich’s baby was still breastfeeding at the time, which made the separation more difficult. The next day, her children used her cell phone to call an aunt, who went to get them. But it would be three days before ICE released Cauich so she could reunite with her children. Three years later, she still sees the effects.

“My children are still recovering from the trauma of seeing their mom taken away and being left all alone. My son who is now six starts trembling when he sees a police officer. He trembles all over! They have that in their mind and it has not been erased,” said Cauich.

The kind of trauma affecting Cauich’s children is becoming more and more common in American households. And for many children, the separation is much longer than three days. More than 5,000 children are estimated to be in foster care with a deported parent or a parent in detention. Some children are separated from their parents when detained while crossing the border and sent to a separate facility for minors, said María José Soerens, a licensed mental health counselor working in the state of Washington.

“I had a woman who crossed the border with her child and they were separated. I am talking about a 2 year old. They were taken to two different centers. For 8 months, they did not know what happened to the child. 8 months. In the life of a two year old,” said Soerens.

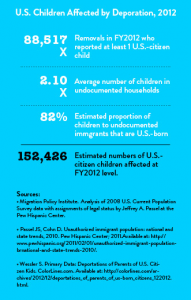

According to a recent study by Human Impact Partners, 600,000 U.S. citizen children had a parent or guardian detained or deported between 1998 and 2012. If detention and deportation continues at current levels, more than 150,000 U.S. citizen children will experience the loss of a guardian or parent in the next year alone, according to the report.

Furthermore, the authors of the report, titled “Family Unity, Family Health,” contend that a large majority of those children will experience declining mental and physical health and difficulty in school. The report estimates that more than 100,000 children will experience withdrawal, or detachment from their families, as a result of a parent being deported, and a number of them will experience aggression and anxiety. In addition, over 40,000 children will suffer a decline in their physical health, due to the separation, says Lili Farhang, one of the report’s authors. Farhang holds a Master’s in Public Health. She says income is closely linked to health outcomes.

“You can basically say that if income drops off this amount in a family, the odds of health declining are this much. The loss of a breadwinner in one of these families translates into a loss of income for that family and a loss of income essentially translates into a decline in health,” said Farhang.

The loss of income would also lead to over 125,000 children living in homes without enough food to go around, which could lead to hunger and malnutrition, said Farhang.

Dr. Alan Shapiro is the Senior Medical Director of Community Pediatric Programs, the flagship program of Children’s Health Fund and Montefiore Medical Center in New York. He describes the scenario this way:

“Take a family where one of the parents is documented or a resident, and one is undocumented,” said Shapiro. “Say the father gets deported. All of a sudden the household income decreases by 50 or 70 percent. So the mom can’t pay the rent in, say, a month or so, and ends up in a homeless shelter. So the two children, who were living in an apartment, in stability, end up in a homeless shelter, which could very easily be in a completely different part of the city than where they grew up. They are separated from their home, their schools, their friends, and their clinics. It could mean hours and hours of traveling to make appointments.”

On the other side of the country, in the Pacific Northwest, María Jose Soerens has interviewed dozens of families who have been affected by immigration enforcement policy. Soerens has spent the past five years almost exclusively conducting psychological evaluations of immigrants in the state of Washington to use for their immigration cases. She says the mental health of children is affected from the moment their parents are detained, oftentimes in front of their sons and daughters.

“In their world, only bad people go to jail,” says Soerens. “So it is very confusing for a child to understand why their parent, who is a good person, is being taken to detention. Frequently, in cases when children are seeing their parent detained, they try to speak up and they say, ‘Why are you taking my mommy or my daddy? My mommy is a good person.’ Or sometimes after the parent is detained, the child is angry with their parents because they think they did something wrong.”

Soerens recalls one family in particular, in which both parents were undocumented, and the father had created a carpeting business himself, in which she says he was able to make over $100,000 a year and support his family. He had two daughters and a son, all under the age of 9, and Soerens recalls the children were excelling in school. The oldest daughter had dreams of becoming a doctor or a lawyer.

“And then he was detained, and of course, because he was in detention, he was not able to support his family,” Soerens recalls.

Unable to support themselves, the mother and children went to live with a relative.

“Their entire world changed,” said Soerens. “They started having problems at school, and they were on food stamps. The youngest child who was 4 at the time presented separation anxiety. The older girls did not have spaces to talk about the family separation so they were also suffering anxiety. They wanted to protect their family first, so they saw anyone outside the family as a threat. They were extremely sad, they were struggling at school.”

In a survey conducted as part of the research for “Family Unity, Family Health,” three out of four undocumented parents who responded said their kids showed symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. More than one third of undocumented parents reported their children were afraid all or most of the time, and more than half reported their kids were anxious all or most of the the time, because of their parents’ legal status.

“From a mental health perspective, the only categories we have to speak about this are depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, ADHD, but I feel that those categories do not truly honor what is happening at a national level,” said Soerens. “In those conditions, to be honest, there is not much we can do as mental health professionals. The source of the stress is completely outside of the family. How can you teach a child to cope with conditions that are completely outside of anyone’s power?”

The stress of living with constant fear of one’s parents being taken away can end up causing major health problems in the long run. Soerens, Farhang, and Shapiro point to studies such as the Center for Disease Control’s Adverse Childhood Experiences study and another study by the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard. Both studies show that living with constant unmitigated stress in childhood can sow seeds that can erupt as major health problems down the road.

“You can’t really have a healthy adult if they had an unhealthy childhood. These things accumulate inside of them, and there’s physiological responses. For example, through something called cortisol,” said Farhang. “So if you’re feeling really stressed and it goes off the charts, it can translate into heart disease high blood pressure and all of these health outcomes that are really expensive and are totally avoidable if you can mitigate some of these stressors.”

Studies show stress can be mitigated by loving, caring providers. But in many cases that Dr. Shapiro has seen in New York City, the children of immigrants end up in homeless shelters after one or both parents is detained or deported. And the fear of separation can only be mitigated by removing the threat of deportability, said Soerens.

The main way to mitigate the stress, they say, is through comprehensive immigration reform, with a quick pathway to citizenship, access to healthcare, and discretion on the part of judges and immigration officials to consider children. All too often, Soerens said, children are left out of the equation.

“That’s the disheartening part of the immigration system,” said Soerens. “All of the effects we have seen on children do not carry much weight.”

California last year passed a law to allow detained parents to remain with their children and keep them out of the child welfare system. And ICE issued a directive this past August which urges officers to consider whether an immigrant is a parent of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident child during enforcement proceedings and spells out the ways parents should be allowed to reunify with their children.

But in order to make a real change in the lives of children, the government has to go farther, says Dr. Shapiro:

“What you’re actually doing, is really damaging the lives of U.S. citizens who are their children. That’s insane. Why would we not want our children to have the advantages of every child? Why would we set up a policy that purposefully puts them at a disadvantage?”

This article was reported as part of a fellowship from the Institute for Justice & Journalism.