Scott and Sandy Van Veldhuizen’s 12-year-old son died following complications during a tonsillectomy in 2016. (Michael Zamora/The Des Moines Register)

The surgery went fine. Her doctors left for the day. Four hours later, Paulina Tam started gasping for air.

Internal bleeding was cutting off her windpipe, a well-known complication of the spine surgery she had undergone.

But a Medicare inspection report describing the event says that nobody who remained on duty that evening at the Northern California surgery center knew what to do.

In desperation, a nurse did something that would not happen in a hospital.

She dialed 911.

By the time an ambulance delivered Tam to the emergency room, the 58-year-old mother of three was lifeless, according to the report.

If Tam had been operated on at a hospital, a few simple steps could have saved her life.

But like hundreds of thousands of other patients each year, Tam went to one of the nation’s 5,600-plus surgery centers.

Such centers started nearly 50 years ago as low-cost alternatives for minor surgeries. They now outnumber hospitals as federal regulators have signed off on an ever-widening array of outpatient procedures in an effort to cut federal health care costs.

Thousands of times each year, these centers call 911 as patients experience complications ranging from minor to fatal. Yet no one knows how many people die as a result, because no national authority tracks the tragic outcomes. An investigation by Kaiser Health News and the USA TODAY Network has discovered that more than 260 patients have died since 2013 after in-and-out procedures at surgery centers across the country. Dozens — some as young as 2 — have perished after routine operations, such as colonoscopies and tonsillectomies.

Reporters examined autopsy records, legal filings and more than 12,000 state and Medicare inspection records, and interviewed dozens of doctors, health policy experts and patients throughout the industry, in the most extensive examination of these records to date.

The investigation revealed:

- Surgery centers have steadily expanded their business by taking on increasingly risky surgeries. At least 14 patients have died after complex spinal surgeries like those that federal regulators at Medicare recently approved for surgery centers. Even as the risks of doing such surgeries off a hospital campus can be great, so is the reward. Doctors who own a share of the center can earn their own fee and a cut of the facility’s fee, a meaningful sum for operations that can cost $100,000 or more.

- To protect patients, Medicare requires surgery centers to line up a local hospital to take their patients when emergencies arise. In rural areas, centers can be 15 or more miles away. Even when the hospital is close, 20 to 30 minutes can pass between a 911 call and arrival at an ER.

- Some surgery centers are accused of overlooking high-risk health problems and treat patients who experts say should be operated on only in hospitals, if at all. At least 25 people with underlying medical conditions have left surgery centers and died within minutes or days. They include an Ohio woman with out-of-control blood pressure, a 49-year-old West Virginia man awaiting a heart transplant and several children with sleep apnea.

- Some surgery centers risk patient lives by skimping on training or lifesaving equipment. Others have sent patients home before they were fully recovered. On their drives home, shocked family members in Arkansas, Oklahoma and Georgia discovered their loved ones were not asleep but on the verge of death. Surgery centers have been criticized in cases where staff didn’t have the tools to open a difficult airway or skills to save a patient from bleeding to death.

Most operations done in surgery centers go off without a hitch. And surgery carries risk, no matter where it’s done. Some centers have state-of-the-art equipment and highly trained staff that are better prepared to handle emergencies.

But Kaiser Health News and the USA TODAY Network found more than a dozen cases where the absence of trained staff or emergency equipment appears to have put patients in peril.

And in cases similar to Tam’s, upper-spine surgery patients have been sent home too soon, with the risk of suffocation looming.

In 2008, a 35-year-old Oregon father of three struggled for air, pounding the car roof in frustration while his wife sped him to a hospital. A Dallas man collapsed in his father’s arms waiting for an ambulance in 2011. Another Oregon man began to suffocate in his living room the night of his upper-spine surgery in 2014. A San Diego man gasped “like a fish,” his wife recalled, as they waited for an ambulance on April 28, 2016.

None of them survived.

Spinal surgery patient McArthur Roberson, 60, lost more than a quart of blood during the operation and struggled to breathe after surgery, his family claimed in a lawsuit. He died on the way home.

If he “had been observed in a hospital overnight,” said Dr. Daniel Silcox, an Atlanta spine surgeon and expert for the family in their lawsuit, “his death would not have occurred.”

The surgery center denied wrongdoing in the case, which reached a confidential settlement in 2017.

Rekhaben Shah, 67, went to the Oak Tree Surgery Center in Edison, N.J., for a colonoscopy in late 2015. Her oxygen levels plunged, and an anesthesiologist trying to save her could not locate the airway mask or airway scope she needed, according to deposition transcripts in the Shah family’s suit against the center. Shah died two days later in a hospital, according to the ongoing lawsuit. Pictured here, Rekhaben’s children Kaushal (left) and Neha stand with their father, Dharnedra Shah, holding a photo of her. The center and anesthesiologist did not return calls for comment. In a court filing, an expert for the center argued that an obstruction in her larynx made it impossible for anyone to insert a breathing tube. An expert for the anesthesiologist said her actions were timely and appropriate. (Amy Newman/The Record)

Many in the health care field — from doctors to private insurance companies to Medicare — have dismissed the mounting deaths as medical anomalies beyond the control of physicians.

USA TODAY Network and KHN reporters contacted 24 doctors and surgery center administrators about patient deaths and none would answer questions about what went wrong, citing patient privacy laws, or referring reporters to attorneys. Responding to lawsuits around the nation, surgery centers have argued that fatal complications were among the known outcomes of such surgeries. Two centers blamed patients for negligence in their own demise.

Bill Prentice, chief executive of the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, declined to speak about individual cases but said he has seen no data proving surgery centers are less safe than hospitals.

“There is nothing distinct or different about the surgery center model that makes the provision of health care any more dangerous than anywhere else,” Prentice said. “The human body is a mysterious thing, and a patient that has met every possible protocol can walk in that day and still have something unimaginable happen to them that has nothing to do with the care that’s being provided.”

However, Dr. Kenneth Rothfield, board member of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety, said many surgery centers and physicians push the envelope on how much can be done in outpatient centers.

“It’s important to realize that surgery centers are not hospitals,” he said. “They have different resources, different equipment.”

At a hospital, doctors and nurses … know how they are going to respond. These guys at the surgery centers are walking on a tightrope with no safety net.

The explosive growth of surgery centers — which receive $4.1 billion a year from Medicare — has taken place under circumstances some medical experts consider unseemly.

Federal law allows surgery center doctors — unlike others — to steer patients to facilities they own, rather than the full-service hospital down the street. In some cases, doing so could increase the risk to a patient, but double a physician’s profits.

Prentice said physician ownership of surgery centers is a good thing.

“The physicians who practice there are responsible for everything that happens in that surgery center from the moment the patient walks out of their car in the parking lot to the moment they leave,” he said.

But several studies have shown that surgery center doctors who are owners perform operations more frequently. And in lawsuits across the country, surgery center doctors have been accused of taking risks with patients.

Even some who’ve made their living in the surgery center industry have expressed concerns. Dr. Larry Teuber, a South Dakota neurosurgeon who worked as an executive in the surgery center industry for 22 years, said he has watched surgery center owners take on increasingly complex — and lucrative — orthopedic and spinal surgeries, undercutting a nearby hospital’s profits for their own gain.

“When you’re making money doing [complex surgeries] you get on a slippery ethical slope,” Teuber said. “The money overshadows everything.”

“I cry every night. I still miss him,” says Carmen Carrasquillo, Pedro Maldonado’s widow. Maldonado, 59, went to Ambulatory Care Center in New Jersey to have his upper digestive tract scoped. He was discovered unresponsive 10 minutes after the seven-minute procedure, according to his widow’s lawsuit. (Amy Newman/The Record)

The History

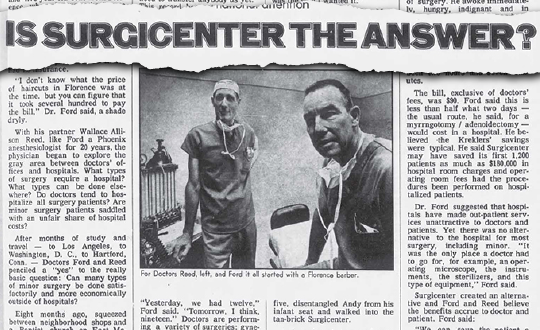

The first surgery center in the U.S. opened in Phoenix in 1970, a place “squeezed between neighborhood shops and a Baptist church,” where, for $90, a child could receive an incision to relieve pressure on the inner ear, The Arizona Republic reported at the time.

The pioneering doctors, John Ford and Wallace Reed, didn’t see why patients needed to be hospitalized for such minor surgeries.

Taking the procedures out of hospitals reduced the cost for patients and insurers because surgery centers don’t require the same level of staffing or lifesaving equipment.

(Story continues below.)

SOURCE: MedPac Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, covering several years

Credit: Jim Sergent, USA TODAY

Medicare helped drive the expansion of surgery centers when it began paying for procedures in 1982.

Then in 1993, Congress encouraged doctors to open surgery centers by exempting them from the second Stark Law, which prevents doctors from steering patients to other businesses they own.

Doctors-turned-entrepreneurs drove early growth, urging their patients to give the centers a chance. Seeing lucrative elective surgeries moving away, hospitals increasingly bought centers of their own. Last year, insurance giant UnitedHealth Group spent $2.3 billion buying a national surgery center chain.

The centers have been popular with patients, who enjoy the convenience and personalized care. Doctors say they like the ease of planning operations without unexpected trauma surgeries upending the schedule. And surgery centers have thrived even as hospitals have battled to contain the spread of infections.

Today, there are 5,616 Medicare-certified centers. The expansion has come despite lingering safety concerns. In 2007, Medicare noted that surgery centers “have neither patient safety standards consistent with those in place for hospitals, nor are they required to have the trained staff and equipment needed to provide the breadth of intensity of care. …” Some procedures are “unsafe” to be handled at surgery centers, the report concluded.

Medicare advised the centers to transfer patients to hospitals when emergencies arise. Only a third of surgery centers participate in a voluntary effort to report how often that happens. They sent at least 7,000 patients to the hospital in the year that ended in September 2017, a KHN analysis of surgery center industry data shows. Not all survive the trip.

In the 21st century in the USA, a doctor doing a surgery on a patient has to call 911? Give me a break. … It’s just absolutely ignorant.

They include James Long, 56, who had no pulse when an ambulance came to the Colorado surgery center where he’d undergone more than five hours of lower-spine surgery in 2014, according to the center’s medical records provided to the family’s attorney.

The state reviewed the case and cited no deficiencies. Jen Kenitzer, the Minimally Invasive Spine Institute administrator, said the center has “extensive procedures in place to respond quickly and appropriately” in emergencies.

Yet Long’s loved ones remain troubled by the case.

“In the 21st century in the USA, a doctor doing a surgery on a patient has to call 911?” said Robin Long, his ex-wife, who did not sue the center. “Give me a break. … It’s just absolutely ignorant.”

Rekhaben Shah, 67, died following a colonoscopy at Oak Tree Surgery Center in Edison, N.J. Shah was the glue that kept her family together. “We lost everything,” daughter Neha Shah says. (Amy Newman/The Record)

Preparation Under Par

Patients enter hospitals with heart attacks, gunshot wounds and traumatic injuries. There, doctors and nurses become skilled at saving lives in emergencies.

Doctors in surgery centers may excel at the procedures they perform most often. But the centers aren’t always prepared and sometimes struggle in a crisis, according to a review of Medicare records and more than 70 lawsuits.

Health inspectors working on behalf of Medicare have discovered 230 lapses in rescue equipment or training regulations at surgery centers since 2015.

A center in California had empty oxygen tanks. One operating on children in Arkansas didn’t have a pediatric tracheotomy set to restore breathing; another lacked pediatric defibrillator pads to shock hearts back into rhythm.

In an ongoing lawsuit against her and the center, anesthesiologist Dr. Yoori Yim testified that she came up empty-handed on Dec. 23, 2015, when grappling to find the right-sized airway tube to save a patient who had stopped breathing.

Rekhaben Shah, 67, had come to Oak Tree Surgery Center in Edison, N.J., for a simple colonoscopy.

Yim tried a variety of methods to help Shah breathe, with limited success. From the moment Shah stopped breathing on the operating table, 33 minutes passed before a paramedic effectively inserted a breathing tube, according to medical and EMS records.

Paramedics responding to the center’s 911 call had to use a video GlideScope to see inside the patient’s throat, equipment the surgery center didn’t have, court testimony says.

By then it was too late. Shah was removed from life support at a nearby hospital on Christmas Day.

Neither Yim nor the center returned calls for comment. In court records, an expert for the surgery center said Shah’s airway was obstructed and it was cleared around the time the paramedics arrived. He said the GlideScope is not required in New Jersey, nor would it likely have made a difference. An expert for Yim, however, said her actions were appropriate and if a GlideScope had been at the center, “we would probably not be discussing this case at all.”

When emergency crews arrive, surgery centers are not always prepared to receive them.

In Yim’s case, paramedics testified that she refused to move away from Shah and allow them to attempt lifesaving measures.

In Florida, paramedics who rushed to a surgery center after its usual operating hours hit a locked door while a patient inside gasped for breath. The 55-year-old remains in a vegetative state.

In 2016, paramedics arrived at West Lakes Surgery Center in Iowa as staff tried to revive 12-year-old Reuben Van Veldhuizen after he experienced complications during a tonsillectomy, according to a Medicare inspection report.

One paramedic told state inspectors she had to ask who was in charge of the resuscitation efforts. No one replied, the inspection report says.

The boy made it to the hospital 37 minutes after the surgery center staff called 911. There, he was pronounced dead.

The family filed suit, alleging that the center and anesthesiologist erred in giving the boy an anesthetic that carries a warning about cardiac arrest risk in young boys.

At their home in Oskaloosa, Iowa, Scott and Sandy Van Veldhuizen sit on a bench given to them by families of children who played sports with their son Reuben. (Michael Zamora/The Des Moines Register)

n court records responding to the lawsuit, the surgery center and anesthesiologist said Reuben’s death was a result of “pre-existing conditions, acts of others, or conditions over which (Defendants) had no control or responsibility.”

Yet lawyers who sue the centers and scrutinize their internal records say they often see deadly delays in care.

Pedro Maldonado, 59, went to Ambulatory Care Center in New Jersey to have his upper digestive tract scoped. He was discovered unresponsive 10 minutes after the seven-minute procedure, according to his widow’s lawsuit.

A football and a pinwheel are among the decorations on Reuben’s grave at Evergreen Cemetery in Leighton, Iowa. (Michael Zamora/The Des Moines Register)

It took surgery center staff 25 more minutes to start CPR, according to a lawsuit that Philadelphia attorney Glenn Ellis filed on behalf of Maldonado’s widow. Twenty-seven more minutes passed before Maldonado was wheeled into an ER, the widow’s ongoing suit alleges. Maldonado never regained consciousness.

Reached by phone, a center administrator declined to comment. In a legal filing, the center denied claims of wrongdoing.

“At a hospital, doctors and nurses … know how they are going to respond,” Ellis said. “These guys at the surgery centers are walking on a tightrope with no safety net.”

Pedro Maldonado, 59, of Vineland, N.J., went to Ambulatory Care Center on March 26, 2015, for an examination of his upper digestive system. According to his widow’s lawsuit against the center, he was unresponsive 10 minutes after the procedure and transferred to a hospital, where he remained in a coma and died on April 3. The suit alleges he was not an appropriate candidate for a procedure at the center. The center denied the claims in court records, arguing that Maldonado’s injuries were “caused by pre-existing conditions over which this defendant had no control.” (Amy Newman/The Record)